Slowly sailing east from Pirates Cove, Alabama, with the intention of bumping into places interesting.

At around thirty-five feet long, the Wharram Tangaroa is certainly not a dinghy, but she does share some dinghy like qualities. For example, with a draft of only two and half feet, if we run aground I can jump in the water and push us off. And, to be honest, there has been a couple times where the depth of water and choice of direction have been at odds.

All sails can be easily raised and lowered by one person, as can the anchor with the help of a winch to pull it from sucky mud. The ketch rig balances well, and helps tremendously when tacking through light wind.

‘Curious’ is not a boat that encourages speed or a rushed schedule. She has enough volume in the hulls to accommodate long distance cruising, but overall is small enough to gunk-hole along the coast like a sailing dinghy.

We are not coastal cruisers in the traditional sense. We are dinghy cruisers who happen to be able to sleep aboard in a full sized bed and cook in a wrap around galley. My schedule is defined by which beach we’d like to stop at, our navigation is done in shade, and our overall distance ambition is an ever changing concept.

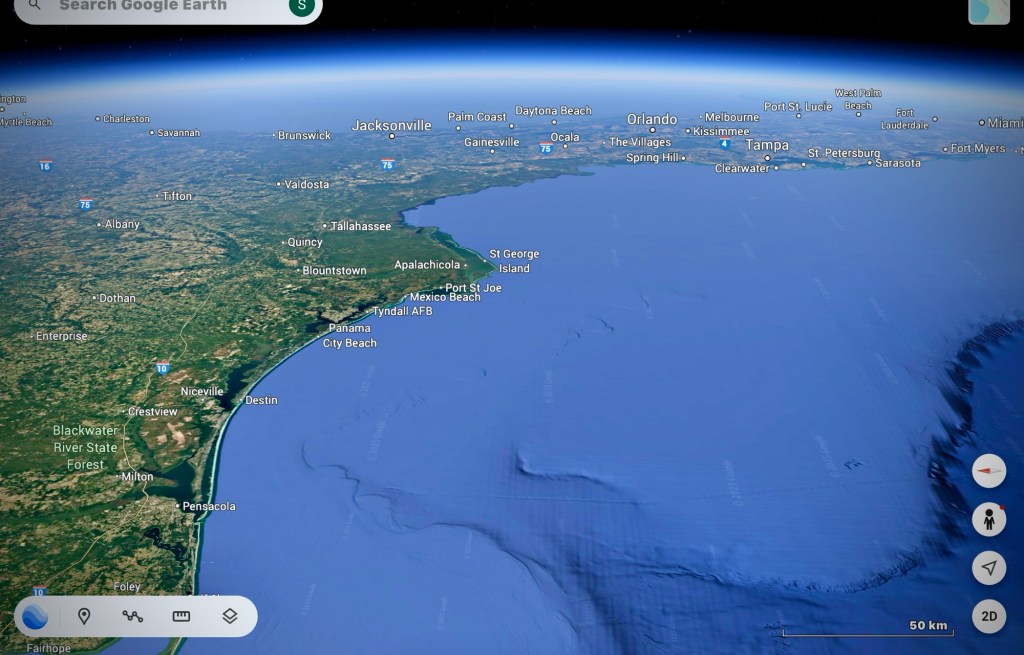

The western coast of Florida—beginning roughly around Perdido Bay and stretching east then south in broad, slow waters—is a place uniquely suited to shallow draft boats and slow days. It is not dramatic coastline. There are no majestic cliffs throwing themselves into the sea with crashing waves, no lighthouses with heroic backstories, no fat ocean swells coming from the Gulf of Mexico. Instead there is water that behaves itself, land that doesn’t ask for much, and an endless series of places where a shallow-draft catamaran can slip in, drop the hook, and immediately forget what day it is.

Which for me happens fairly often.

Heading out on a small adventure

This western end of the Florida panhandle and coastal Alabama is a civilized place to provision, repair, delay departure, and find reasons not to leave. The shoulder seasons of Fall and Spring are unbelievably comfortable weather wise. The weather forecasts however, are largely theoretical.

The Gulf Coast, at least in this stretch, operates on a system of how much, and from which direction the wind blows. The winds control the water depth more than tides, the tides arrive whenever they please, and squalls behave like drunks in a bar. They turn up, make a mess, then disappear. This makes it ideal for people like me, who prefer sailing plans that can be altered mid-sentence.

When we finally leave Pirates Cove, our Tangaroa slides along with the soft competence of a boat that has done this before and doesn’t feel the need to comment on it. The water shifts from forest greens to coastal blues with something resembling tea with too much milk in various places. The shoreline gets a little more remote. The buildings retreat. Trees and beaches take over.

Progress becomes optional.

The Gospel of the Dinghy

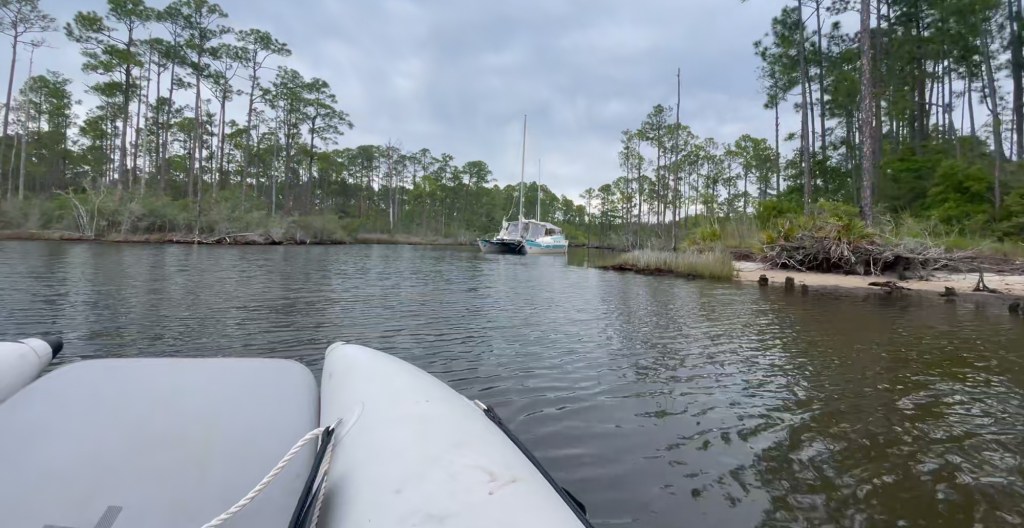

On a boat like this, the dinghy is not just an accessory. It is the primary means of resupply and exploring the really shallow places. The big boat is for sleeping, cooking, fixing things, and arguing with my cat about anchor scope. The dinghy is for jaunting about.

Florida’s west coast is riddled with shallow bays, creeks, passes, and unnamed bits of water that appear to exist solely to reward curiosity. The Tangaroa can nose into many of them, and the dinghy can go everywhere else. These little bays are shallow enough that stingrays ripple the surface when they scurry away and sea grass covered mud flats are home to Blue Crabs, Speckled Trout, and Manatees when deep enough. Skinny creeks that are narrow enough to make you question your choices but not enough to make you turn around. Even when a 6-8 foot alligator launches from the bank 20 feet from the dink.

This is where the Wharram design shines—not because it is fast (it can be), or stable (it is), but because it frees you from the tyranny of marinas. You anchor somewhere quiet, lower the dinghy, and the coastline opens up like a long conversation you don’t have to finish.

Some days the dinghy trip ashore is a purposeful affair—water jugs, groceries, a cold beer at a bar. Other days it is entirely recreational. You row simply because the water looks pleasantly rowable.

Anchoring as an Art Form

Anchoring along this coast is less about technique and more about manners. You choose places where your presence feels appropriate. Places that won’t mind you staying a while, away from the crowds and condo’s.

There are broad bays where you can swing all day without bothering anyone. Narrow creeks where the trees lean in close enough to overhear your thoughts. Sand-bottom coves where the anchor sets with a quiet confidence that makes you trust it more than you probably should.

The Tangaroa, with her twin hulls and shallow draft, settles into these places without fuss. She does not roll. She does not complain. She allows you to forget that boats are supposed to move.

At anchor, time stretches. Breakfast becomes a relaxing process. Reading becomes an activity that takes up way too much time. Maintenance tasks expand to fill whatever space the day provides.

And then there is the dinghy again—waiting patiently, like a dog who knows you’ll eventually want to go somewhere.

Shore Life, Lightly Touched

The west coast towns are not destinations so much as interruptions. Small places with boat ramps, bait shops, post offices, and restaurants that serve food you didn’t know you missed until you smelled it from the dinghy.

You come ashore salty, and slightly out of step with land-based time. People are kind. They’re curious, but not intrusive. They ask where you came from, then where you’re going, which is the correct question.

There is a particular pleasure in tying up the dinghy somewhere unofficial—no signs, no docks, just a bit of sand that looks as though it has been used before and will be used again. You walk into town knowing you’ll be leaving the same way you arrived: quietly.

Weather, Briefly Considered

Weather along this stretch is a background character. It exists, it has opinions, but it rarely insists on being the center of attention, unless it’s towering up and dark. Morning calms, afternoon breezes, the occasional rain squall that announces itself politely before passing through.

You learn to read the horizon rather than the forecast. You notice how the air feels. How the birds behave. How the boat feels as it dances with the wavelets at anchor.

Sailing days are chosen not because they are perfect but because they seem agreeable. The Tangaroa responds to this approach with steady, forgiving performance. She will sail in very little wind and tolerate quite a bit more than you’d planned for.

When conditions turn unfriendly, there is almost always somewhere nearby to hide. A bay, a hook behind an island whose name you never learn.

The Pleasure of Not Getting There

Progress southward is incremental. Measured in familiar anchorages and new ones that feel familiar immediately. You may travel ten or twenty miles in a day. Or none at all.

This is dinghy-style cruising: the big boat is transportation between playgrounds. The coast reveals itself in pieces small enough to appreciate. You learn the texture of different waters. The smell of different shorelines. The way the light changes in the late afternoon when the sun slides down into the gulf instead of cliffs.

You stop caring where you are on the chart and start caring how the sun feels on deck.

Why This Coast Works

Florida’s western coast doesn’t call for heroics. It rewards attentiveness. It favors shallow draft, patience, and a willingness to spend an afternoon going nowhere in particular.

A Wharram Tangaroa fits this environment not because it was designed for Florida specifically, but because it was designed for people who value access over speed and simplicity over convenience. It’s a boat that forgives indecision and encourages lingering.

Cruising here feels less like travel and more like temporary residency. You are not passing through so much as borrowing space.

Evening

At the end of the day, the dinghy comes back aboard or is tied off astern, depending on mood and mosquitoes. The anchor holds. The light fades. The sounds shift from boats to birds to something you assume is a fish but could be anything.

You cook something simple. You eat it slowly. Sip a little rum for captains hour. Then sit and watch the water change color until it decides to stop.

Tomorrow you might sail. Or you might not. Either way, the coast will still be there, doing what it does best: offering just enough to make staying worthwhile.