When I first moved on board Curious, I was fairly certain I knew what I was doing.

Not in a competent sense—there was never any real danger of that—but in a conceptual one. I believed I was embarking on a sailing journey. A boat, nautical charts, weather, and maybe a bit of hardship, things that could be summarized neatly for other people later. Sailing, by its nature is very good that way, it gives shape to a story. It implies progress, direction, and intention. Something I’ve been missing for a very long time.

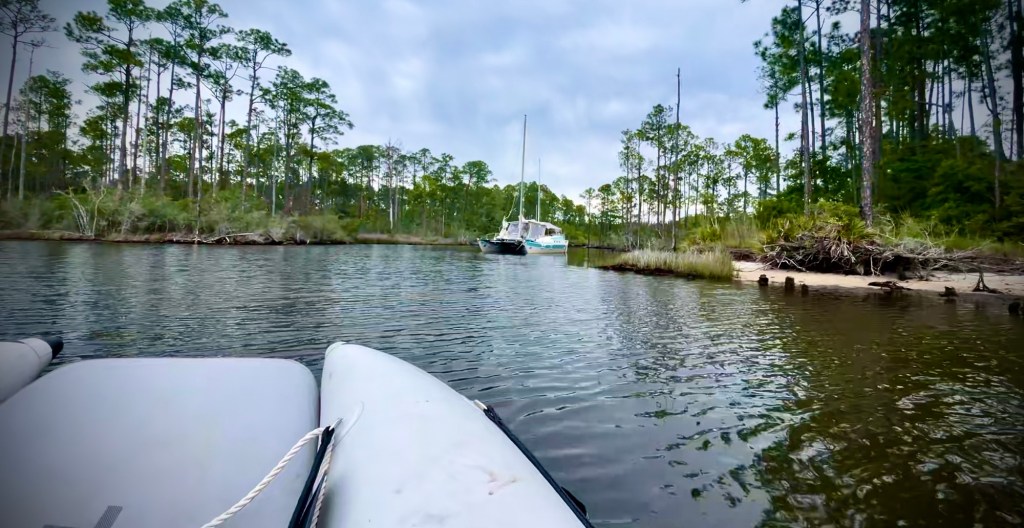

It turns out sailing has shown itself to simply be the delivery system. A way of changing the backyard scenery when the time felt right.

I didn’t realize this at first, because the initially the days supported those assumptions. Journeys to be plotted, to-do lists that demand attention. There is gear that must be bought or replaced, or even fixed, then replaced again. There are routes to be plotted, then balanced against weather. All of this feels like you’re doing something, and it’s all very reassuring.

You can tell people you’re “out cruising,” which sounds purposeful and romantic , even if you’ve only gone ten miles and anchored up in a bay that you’ve been to dozens of times before and know like the back of your hand.

In the beginning, live aboard, full time sailing does what all new projects do: it keeps you busy enough that you don’t ask inconvenient questions.

Those questions arrive later.

They tend to show up once boat-life is no longer novel, once the basic mechanics of daily life have settled into known, predictable, sequences and processes. And once you’ve spent enough time staring at the same piece of water that it stops feeling like scenery and starts feeling like manicured back yard.

That’s when I started to realize that this was never really about sailing at all.

Sailing, as it turns out, occupies very little of the time.

I don’t mean this metaphorically. I mean it in a very literal way. The actual act of moving the boat under sail; adjusting sheets, tweaking sail shape, enjoying the sense of free movement. It makes up a surprisingly small percentage of life aboard. Most days don’t involve sailing. Most time is spent at anchor. Waiting. Fixing things that were fine yesterday. Making small decisions that feel unimportant in the moment but somehow determine the shape of the entire day.

If this were truly a journey all about sailing, I would be sailing much, much more.

Instead, I spend an unreasonable amount of time with the boat dancing on the anchor, doing nothing in particular, and thinking thoughts that have no obvious connection to boats.

At first, I assumed this new reality was a temporary thing. A lull. The calm before the next leg, a new destination, the next chapter where something would happen. Sailing culture certainly encourages this belief. There’s always an implied horizon, even when no one is quite sure what’s on the other side of it. I suppose the mystery is a huge part of attraction and romance.

However, the longer I stayed out here, the harder it became to pretend that the actual sailing was the point.

The sailing is more like the excuse, a means to an end.

It’s the socially acceptable wrapper for a way of living that would otherwise be difficult to explain. “I live on a boat” is a complete sentence. It satisfies curiosity, and generates dreams. It prevents follow-up questions, most imaginations explain the why. It implies competence, even if that implication is wildly optimistic.

What it doesn’t explain is why I’m perfectly content to sit at anchor for days, even weeks, just watching the sun rise and set, watch the creatures of this world do creaturely things, and nothing else.

Or why I’ve stopped comparing time to distance traveled.

Or why the moments that stay with me have nothing to do with wind direction or boat speed.

Somewhere along the way, the journey has quietly changed character.

I honestly didn’t notice when it happened. There was no announcement. No dramatic moment where I realized everything I thought I was doing was counter to the original dream. It was more like discovering that the background noise I had been tuning out was actually the main story.

The boat stopped being the subject and became the condition.

And once I realized this, the questions changed.

Instead of asking where I was going next, I realized I felt no urgency about going anywhere at all. Instead of worrying about whether I was “making progress,” I began wondering why physical progress was a defining attribute.

This is an uncomfortable shift for me, because a sailing journey comes with built-in validation. You’re doing something, going somewhere. You can mark it out on a chart. You can summarize it in a way that sounds active and adventurous.

This quieter, internal journey offers no such evidence.

No one claps because you stayed put and thought about something, or nothing, for three days. There’s no logbook entry for realizing that you don’t actually want the original dream. No nautical term, that I’m aware of, for spending an afternoon doing nothing and finding it completely okay.

If anything, this kind of journey can look suspicious from the outside.

It can resemble indecision. Or laziness. Or failure to “make the most” of an opportunity. Sailing is supposed to be dynamic. Romantic. Full of sunsets and motion and meaningful hardship. There’s a script for this, and nearly all who read it, and are not actually living it, believe it.

But real life aboard is mostly quiet, and that quiet has a way of dismantling those scripts.

When you remove the constant input of life on land—errands, obligations, casual social noise—you’re left with a lot of unstructured mental space and time. That void doesn’t automatically fill itself with wisdom, or clarity.

Sometimes it just gets filled with boredom. Sometimes with mildly troubling questions. Sometimes with nothing at all.

And, if you give it long enough, it reveals that the journey you thought you were on was misnamed.

This isn’t just a ‘Sailing Journey’.

It’s a journey of tolerance for stillness and extended time.

Of discovering how much activity, and input, you actually need.

Of finding out what remains when you remove the pressure to optimize every moment; in thought, or action.

I didn’t set out to learn any of this. I certainly didn’t plan to write about it. If I had been more honest with myself at the beginning, I might have admitted that I just wanted a different set of problems. Preferably ones that involved wind and water instead of whatever was waiting for me on shore.

Sailing was supposed to be the solution.

Instead, it turned out to be a very effective mirror.

A simple boat has an irritating habit of reflecting things back at you. Not dramatically. Not in a self-help way. Just quietly, over time. You notice how you react to inconvenience. How you deal with uncertainty. How you fill—or avoid—long stretches of unclaimed time.

You also notice how little you actually need to be moving to feel alive.

This realization doesn’t arrive as an epiphany. It creeps in slowly, like a tide creeping over the sand flats. One day you realize you haven’t checked what day of the week it is, because it doesn’t matter. Another day you realize you’re more interested in the quality of your mornings than the distance you covered last week.

Eventually, you realize that the next anchorage will be not meaningfully different from the current one. The change of scenery will be welcoming different, but essence of the moment remains the same.

That’s when, for me, the idea of a sailing journey really took on a different personality.

Because journeys, as we tend to define them, require specific destinations. Or at least milestones. Some sense that the movement itself is the story. But when movement becomes optional, the narrative evolves.

What’s left is not a journey in the traditional sense, but a way of inhabiting time. Reading over this while editing, I realize it sounds a bit wanky, but it makes sense at the time.

Living aboard has taught me that most of life happens in the margins—between plans, between movements, between the things we are trying to achieve.

To be perfectly candid, this wasn’t what I signed up for.

I was looking for wind and water and romantic inconvenience. I signed up for the idea that movement would carry meaning with it, the way it does in books and stories and other people’s carefully edited lives.

What I got instead was slower, less intense. Not easily summarized, nor productive or particularly impressive.

But it does feel accurate.

Accurate to the pace at which things actually changed.

Accurate to the way understanding tends to arrive—not in breakthroughs, but in small, unremarkable adjustments. Accurate to the realization that you can live quite fully without going very far at all.

So no, this isn’t a sailing journey.

Of course the sailing happens. It keeps the boat from becoming a very small, floating house permanently stuck in one place.

But it’s not the main point.

The point, if there is one, seems to be learning how to stay—physically, mentally, attentively—without immediately reaching for the next thing. To let days just do their thing and slowly pass by. To accept that not everything needs to turn into a story with a clean arc.

Of course I still sail. There’s an undeniable joy to it. But I’m also just as happy to motor somewhere. Simply moving around and living on the water.

But I no longer mistake that motion for meaning.

What this journey has shown me so far, is that a lot of the fondest memories have happened mostly while the anchor is down.

And that’s taken me much farther than sailing ever has.