There’s a certain kind of magic in writing from a hammock strung between the masts of a small sailing catamaran. The gentle movement of the water, the whisper of the wind in the rigging, the occasional splash of a curious fish — they all conspire to create an atmosphere that’s equal parts peace and possibility.

For many, the idea of crafting stories or articles from a tranquil anchorage, laptop balanced on their lap and seabirds circling overhead, sounds like a far-off dream. But for those traveling long-term on a boat, it can be a regular part of life.

This is not a romanticized fantasy. It’s a real, tangible lifestyle — always challenging, often rewarding, but constantly inspiring. Here’s what it’s like to write articles from a hammock, and why more writers, digital nomads, and creators are chasing this fluid way of life.

The Setting: A Floating Writing Retreat

Imagine a quiet bay, fringed with mangroves or lined with rugged cliffs. The catamaran is gently tugging at her anchor chain, facing into the breeze. You’re lying in a hammock, strung under the shade of the mainsail boom or in the netting stretched between the bows. The soundscape is soothing — lapping waves, the distant call of gulls, the occasional creak of the anchor bridle.

This is your office.

Instead of traffic or an office copier humming in the background, you have dolphins chasing food nearby or the rumble of a dinghy heading off for provisions. The distractions are different, and often more beautiful, but the work remains the same: throw down many words, re-read, chop out and replace, read again, chop, replace, and again, and again.

The Tools of the Trade (Afloat)

To make this lifestyle work, a few essentials are non-negotiable:

A reliable laptop or tablet.

Solar power, which is gold on a boat. A solid setup with solar panels, charge controllers, and a reliable battery bank means you can keep your gear charged when anchored off-grid full time.

Internet connectivity is critical for research, publishing. Many use mobile hotspots with local SIM cards, Starlink satellite internet, or long-range Wi-Fi antennas to stay connected.

A notebook or journal for those messy brainstorming sessions.

Comfortable seating, including the hammock. On my catamaran, options abound: cockpit cushions, netting between the bows, or feet dangling in the water from the rear swim deck.

With these tools, you can write just about anywhere — at sea, at anchor, or pulled up on a delightfully deserted beach.

Inspiration in Every Direction

Writing from a boat opens your mind in ways not available on land. Living close to the elements sharpens your awareness. You’re tuned in to the rhythms of the weather, the phases of the moon, and the shifts in tide and wind that can change your day.

This awareness seeps into your writing. Even if the articles are not just about sailing or travel, the clarity of thought and reduction in stress can dramatically improve your productivity and creativity.

That said, the stories that unfold around you are often too good not to write about. Maybe it’s the 3 a.m.- 50 knot squall, combined with having dropped the anchor on an old crab pot, and being blown into the beach… and being stuck there for three days. Yep, that did happen.

These stories become metaphors, anecdotes, and color in the work. Hopefully they help my writing be richer, deeper, with a unique perspective.

The Challenges: It’s Not Always Margaritas and Manuscripts

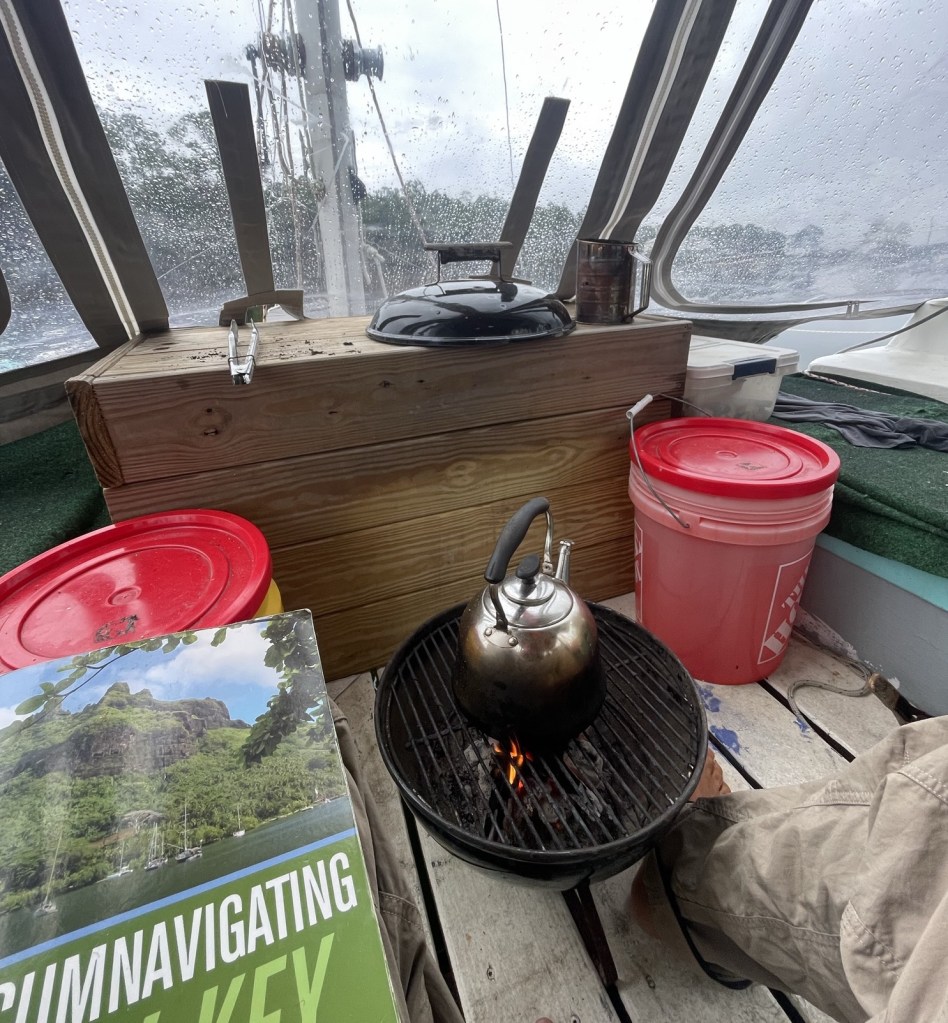

To be real: writing from a hammock on my catamaran is not always idyllic. Some days, it’s plain uncomfortable.

Heat and humidity can make concentration difficult, there’s no air conditioning, especially if there’s no breeze in a hot anchorage. Heat becomes oppressive, your brain fogs up, and your skin feels on fire. Deep cold can have the same effect.

Motion can be distracting. Even at anchor, strange swells can rock the boat unexpectedly. It might feel dreamy to sway in a hammock, but a harmonic can set up, wildly slinging you side to side. Within two swings I’ve been violently thrown side to side with arms and legs flailing like an epileptic spider.

Internet loss can delay deadlines. Although to be fair, it’s usually because I couldn’t be arsed to do the work on time.

You don’t have a desk, or consistent workspace. You learn to be flexible, literally — shifting between cross-legged on an engine box, leaning against a bulkhead, or sitting on sand…and, let’s not forget, the hammock.

Noise is different but it is ever-present. Wind through the rigging can get old quickly. Water slapping against the hull or the dinghy can feel rhythmic or irritating depending on your mood. Rain, or neighbors in nearby boats cranking up their version of ‘music’ can disrupt your train of thought.

But despite these drawbacks, the benefits far outweigh the inconveniences.

Routine and Rhythm: Writing in Sync with the Sea

Living on a boat means living by rhythms: tides, weather, sunrise and sunset. Writing fits into these patterns surprisingly well.

Early morning for me is the golden time to write. The boat is quiet, the world is slowly awakening, and the growing light is gentle. With a pot of coffee and a fresh breeze, maybe some Enigma from the speakers, ideas and thoughts flow freely. It’s a sacred time before the day begins. Dreams from the night before are still fresh, and dreams of the future feel more attainable.

Midday, especially in the hotter climates, are for siestas or swimming, and sometimes boat work. Occasionally writing resumes in the late afternoon or just before sunset. More often though, it’s a cool drink and just watch the world as it happens.

The Freedom Factor

There’s no boss looking over your shoulder. No traffic jam on the way to an office. No beige cubicle walls. You answer to the wind, the weather, and your own motivation. Which in my case can be seriously lacking at times. I’ve always been the kid staring out the window with a chalkboard duster flying my direction.

Writing on a boat demands discipline, but it gives back an incredible sense of freedom. You might spend a week anchored near a town, writing at a table in a local bar, and the another in a remote little bay, swinging in the hammock as you polish the latest jumble of thoughts on the page.

You don’t have to wait for a writing retreat. You’re already living one.

Monetizing the Lifestyle

To support this life, many writers diversify their income streams. Here are a few common ways writers afloat stay afloat financially (I look forward to being one of them!):

Freelance writing for blogs, magazines, and online publications

Content marketing for companies that allow remote work

Writing and self-publishing books, particularly about sailing, travel, or digital nomad life

Running a blog or YouTube channel, monetized via ads, sponsorships, or Patreon

Offering editorial services, like proofreading, editing, or ghostwriting

Apparently the key is to maintain consistency — in delivering work, and managing expectations. Some may never appreciate you’re working from a hammock on a catamaran — and that’s fine. Others may find it fascinating and want to hear more…I like them.

Connection, Solitude, and Stories

Writing on a boat gives you solitude — the kind that fuels introspection and creativity. But it also gives you connection: with nature, with other sailors and people you meet along the way.

And all good stories are born through connection.

Tales are shared over sundowners in the cockpit. Experiences and ideas are traded with fellow cruisers. You get invited into local communities where your outsider eyes notice things others take for granted. All of these moments become fuel for articles, whether you’re creating a narrative essay, cultural commentary, or instructional outlines.

Final Thoughts: The Floating Writer’s Dream

I guess there’s no one-size-fits-all way to live and write from a boat. Some writers are full-time cruisers who work between passages. Others split their time between land and sea. Some are novelists, others are bloggers or journalists. But what they all share is the ability to adapt — to embrace change, learn to appreciate discomfort, and create even when the world beneath them constantly moves.

Writing articles from a hammock on a boat, or on the sand of a beach, it isn’t about luxury. It’s about choice. It’s about choosing a slow pace over speed, balancing presence with productivity, and story over schedule.

And when the sun sets over a glassy anchorage, the stars come out, and your latest article is saved and submitted, you can know one thing for certain: no cubicle in the world can compete with this.