Comfort while living on a sailboat? It isn’t always about systems and hardware and equipment.

For me, it is equally about ambience; music, a favorite drink, and maybe a fire in the Barbecue pit. These things add as much comfort, and a feeling of “home,” as all the other essential components.

That’s not to say a properly functioning nav system or a reliable engine don’t add peace of mind, but peace of mind isn’t exactly the same as comfort. Peace of mind is the absence of dread. Comfort, on the other hand, is the presence of delight.

The world of cruising is filled with people designing their way out of discomfort. They install water-makers and diesel heaters, inverters the size of microwaves, and enough LED lights to illuminate a football field. But the truth is, you can have every gadget a chandlery ever sold and still feel like you’re camping in a fiberglass container.

That’s where ambience comes in.

It’s the quiet things that make life aboard feel less like survival and more like living. For me, it’s the gentle swing in the hammock. The lingering aroma of a Weber BBQ grill still carrying the remnants of steak and onions,…and a cold beer.

The Myth of Equipment-Based Happiness

Ask any long term cruiser what they’re working on this week, and you’ll get a detailed answer involving pumps, tanks, or electrical wiring, and the occasional curse. They’ll speak of “projects” in the same tone that farmers use for “rain.”

Rarely does anyone ever say, “I’m trying to improve the mood.”

And I think that’s a shame, because the mood is what makes the boat feel like home. Comfort isn’t just about temperature or dryness; it’s about atmosphere. You can be cold, wet, and happy if the moment feels right. Think of sitting by a campfire with a blanket, or sharing a beer on a cold beach. The conditions may not be great, but the feeling is.

On the flip side, you can have all the modern conveniences—a diesel heater, running hot water—and still feel lonely, sterile, and vaguely uncomfortable. Although to be honest, as much as I love the spartan, camping style of life, I do get pangs of envy when visiting a friend’s boat with its huge covered living area.

Music, Memory, and the Sound of the Sea

Aboard a sailboat, music takes on a kind of sacred importance. It’s one of the few things that can transport you beyond the sound of halyards and the creak of anchor lines.

Some evenings, I’ll play old jazz or classical guitar, something that blends with the wind in the rigging. Other times it’ll be 80’s classics and I’ll get bowled over by nostalgia, followed by the realization of how old I’ve become.

The Ritual of the Favorite Drink

If sunsets are about ambience and music is about mood, then a favorite drink is about ritual. It doesn’t have to be fancy. I’ve an old sea kayaking mate who raved about his morning instant coffee and powdered milk. I don’t think he’s right in the head.

My favorite ritual involves a thermal mug and something brown—coffee in the morning, rum in the evening, and sometimes they’ll be in the same cup, I think it’s called a Marlin Spike. If there’s nothing of importance to be done for the day, I love the flavor mixture of a rich dark coffee with a splash of Rum with breakfast. It tastes kind of smokey and soft.

Each morning around the time of sunrise, I’ll get up, measure in my coffee grounds, boil the water, and load up my half liter French press. Stir the mixture, then push the plunger down on a slight angle so the lid doesn’t contact the layer of crema. Hold the lid off the coffee and shake the press as I pour to allow the crema to flow in and cover the cups contents. I know it’s wanky, but it’s something I’ve always done, whether back packing, canoeing, or sailing.

There’s something grounding about that small ceremony. It reminds me that while the sea, the mountains, or society may be indifferent, I don’t have to be.

That first sundowner at anchor is always the best. It’s the transition point from doing to being—from being an active sailor back to a lazy human again.

The Wood-stove: Civilization in a Box

If you’ve never had a wood stove on a boat, you might think it’s overkill. If you have, you know it’s the difference between tolerating winter and enjoying it.

As yet I’ve not had one, but I have camped in cowboy style wall tents, small slab log cabins, and lean-to’s heated via a small wood stove. To say I loved that ambiance would be an understatement.

A stove does more than heat a cabin; it creates a sense of welcoming civility. Firelight softens hard edges, the smell of burning wood helps you forget about cold, wet, uncomfortable conditions outside. Even the act of cutting and storing a wood supply feels noble—like you’ve managed to domesticate the world itself, one stick at a time.

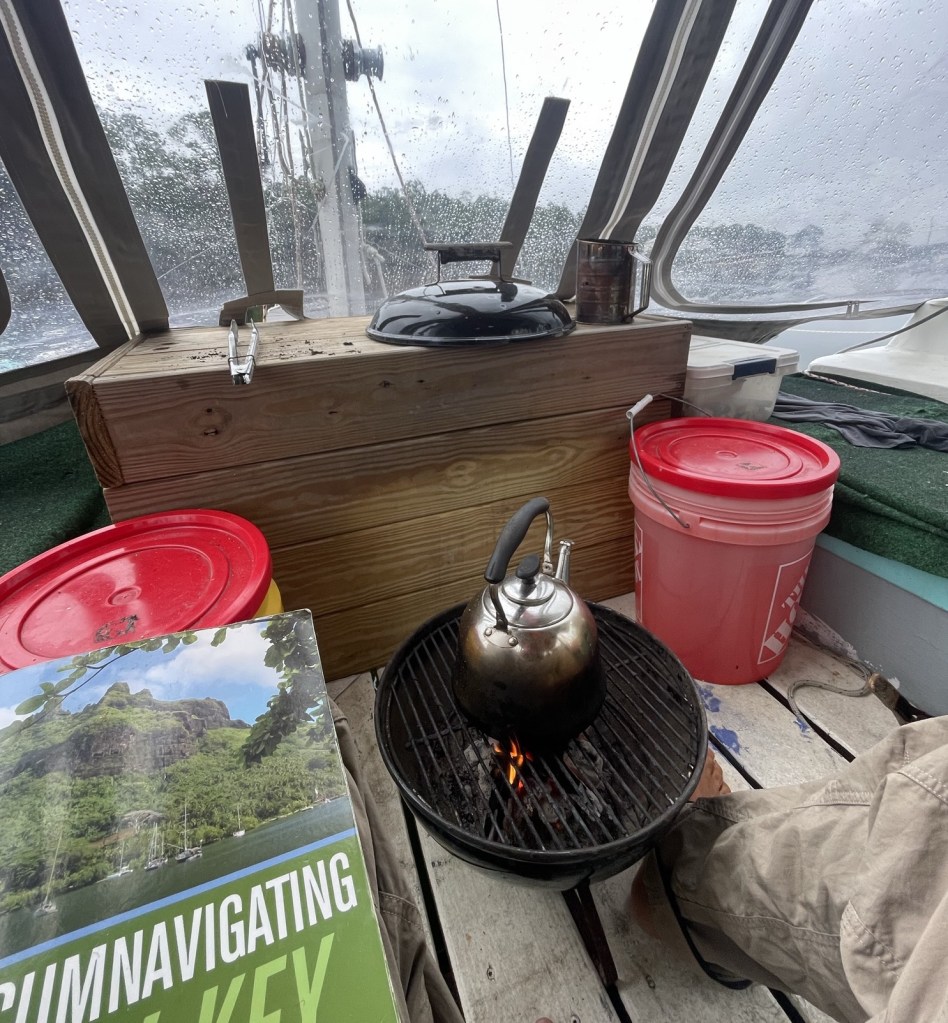

One afternoon, anchored in a quiet cove, I had the little Weber going on deck and food cooking on the grate, doing the slow, patient work that only time can finish. The tarp strung over the deck had the rain whispering against it with cold intent—not loud enough to interrupt thought, just enough to be felt. The air was thick with the mingled aromas of woodsmoke and lamb chops, that particular perfume of a camp shelter that announces you are dry, warm, and in no immediate hurry to be anywhere else. It really is one of my all time favorite situations to be in.

For a while, time stood still. My boat, Curious, was an isolated paradise. My cat had surrendered to the illusion, stretched out near the soft radiating heat of the barbecue, paws tucked, whiskers barely moving. There was no motion worth noting, no tide demanding attention, no clock insisting on relevance. There was no real schedule other than breathing.

I could have been anywhere—a cabin tucked away in the pines, a mountain hut waiting out a storm, or a small town cottage with nowhere to go and nothing expected. It was one of those small, unannounced moments when the difference between land and sea dissolves, and you realize that comfort, like home, is less about geography than it is about warmth, shelter, and a warming fire quietly doing its thing.

That’s the magic of ambience: it tricks the mind into comfort.

The Philosophy of Enough

Living on a boat teaches you to redefine comfort. For me it’s not about luxury; it’s about sufficiency. You start to realize that “enough” is a moving target—and that chasing more can lead to frustration.

I often dream of a bigger boat; B.B.S. The ability to have a center cabin between the hulls is a big attraction. I’m sitting here in the big open saloon of my friends Lagoon 40, writing away as the chilly rain is pelting down outside. I’m protected from the cold and wet. We’re at a dock with the A/C keeping the temperature just right. This kind of luxury does feel good, I admit, and I’m aware of it in the same way you notice weather you don’t expect to last.

My 35 foot Wharram Tangaroa is a wonderful boat, but building a center cabin could start to look a little clunky if not carefully kept to quite a low profile.

Perhaps I could get something bigger like the Wharram Tehini, she’s 51 feet long, very wide with loads of room, and they look oh so very beautiful. I’ll just have to keep dreaming on.

Though a bigger boat generally means bigger expenses, maybe I can find some sort of trade off. Meanwhile, I’m sipping rum beside the fire on Curious, perfectly content with my limited square footage and my flickering fire pit.

Comfort, I’ve learned, isn’t proportional to space or gear—it’s proportional to appreciation.

Weatherproofing the Mind

Being constantly on the water has a way of testing your mood. There are days when the wind howls, the rain comes sideways, and every place onboard feels vaguely damp. On those days, ambience feels more like survival strategy.

You learn to create small islands of comfort in a sea of chaos. Watching a movie curled up under fluffy blankets, a hot cup of something, and a bit of light. Even humor becomes a kind of shelter.

As John Gierach once wrote, “The solution to any problem is to go fishing, and the worse the problem, the longer the trip.” Substitute “fishing” with “dropping the anchor and pouring a drink,” and you’ve got the sailor’s equivalent.

Comfort Is a Choice

In the end, comfort on a Wharram sailboat isn’t a product of what you have—it’s a product of how you live. Anyone can buy gadgets; not everyone can cultivate atmosphere.

You can fill a boat with the best technology available and still be miserable. Or you can fill it with small rituals and simple pleasures and feel rich beyond measure.

It comes down to seeing the boat not merely as, ‘a thing’, but as a home.

Because when the anchor sets and the wind quiets, and you’re sitting there with fog drifting over the water ~ music humming, drink in hand, fire glowing ~ you realize that comfort afloat is less about escaping discomfort, and more about embracing contentment.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about presence.

And that’s something no amount of equipment can buy.